Collector’s Statement

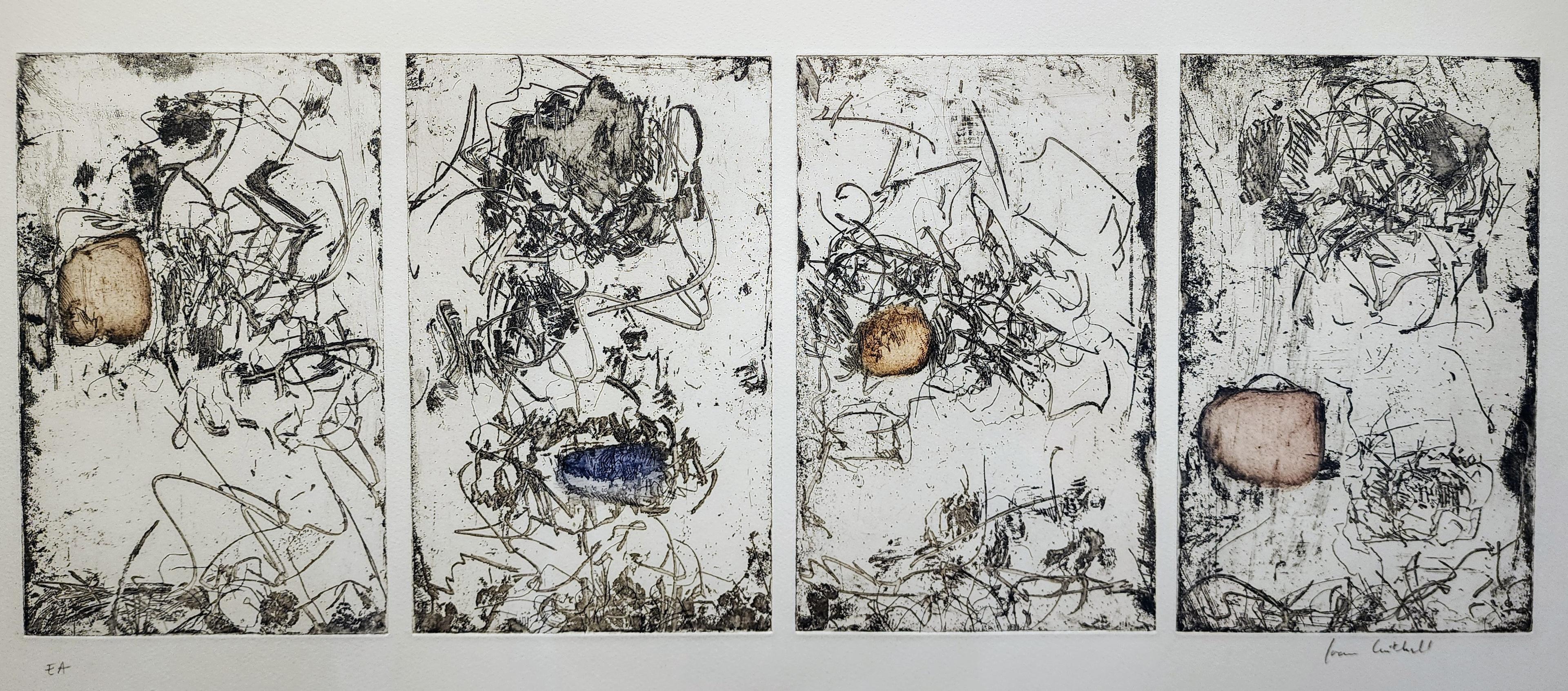

Sunflowers IV (1972) by Joan Mitchell

Perhaps it is because I am a neuroscientist that I think of beauty as something that happens in the mind, and not on a canvas. Or maybe that’s why I am a neuroscientist.

A primary motivation for establishing BAP Art Projects—beyond having an organizational structure so that works in the collection can be made available for loan to galleries and museums—is to create a framework to support ongoing research into Parkinson’s disease, not simply through financial means (though that’s certainly a key part), but by establishing opportunities for cross-disciplinary collaboration between the worlds of art and science.

Over the course of my career, I have spent a great deal of energy and time fighting for research funding. With BAP my aim is to ease that path for others. And so we have structured the organization in a way that allows us to leverage the collection’s value to support the development of innovative new research and treatments for Parkinson’s, and fund the otherwise unfundable.

We are also interested in using BAP as a vehicle to back projects, whether scientific or artistic in nature, that explore how a neurodegenerative disorder like Parkinson’s alters one’s creativity and appreciation of art. This would help those of us without Parkinson’s better understand how it feels to live with the disease. I have a hunch it will also give us insight into how we all appreciate, see, and make sense of art.

In building the collection, I don’t necessarily seek out particular genres, movements, or established names; if you see any trends, they stem from the fact that my journey so far has been a very social one. Some of the themes you may notice—a propensity for women and Indigenous artists, contemporary Canadian, abstraction, and photo-based art—are due to a friend or colleague opening that door for me.

I have built the collection under the guidance of some brilliant artists, gallerists, and curators, largely in Montreal, Toronto, and New York—the art circles I move in. Once those doors have opened for me, what leads me to choose one work over another? It has demanded much self-reflection and many conversations with people more art savvy than I to figure that out, but I think I’m getting close.

The commonality between the works I love, and thus the works BAP acquires, is an emergent property of the manner in which I can appreciate them. I am still finding my way in art, but when I came across LeWitt's concept of “the idea becoming the machine that makes the art,” I found a framework on which to hang my appreciation, my understanding of what I seek. I gain so much from running LeWitt’s scheme in reverse, from looking at the art, discerning the machine, and ultimately the ideas that might have become that machine, whether it’s intended by the artist or of my own making.

You might consider BAP, then, another kind of machine, one for discerning the ways we look at, see, and appreciate art. It is an ongoing exploration into not just my own search to understand how art works on my brain, but also, more generally, the cognitive processes that underlie aesthetic experiences.

When I talk about “discernment” I mean it a little differently from what you might think, if I were to call you discerning while you were looking at one of the works in the BAP collection. Discernment, as I am using it, isn’t about “taste”, as such—it’s the analytical rigour one employs in scientific practice to break down ideas, hypotheses, or problems into their component parts, and find one or more fundamental principles. The goal of discernment in this sense is to systematically uncover meaning with a clarity that wasn’t there at the outset. Lately I have realized that this kind of analytical rigour, so central to my scientific life, is also at the heart of what drives me to enjoy and collect art.

I have this idea that there are three modes of thinking we frequently employ while trying to make sense of the world, whether it’s through science, art, or other meaning-making pursuits. The first, again, is discernment, the kind of rigorous analysis we apply every day in myriad ways. The second mode is one of wonder—a sense of deep curiosity about the world, open to its mysteries and surprises, that impels us to push at the boundaries of rational or conventional thought and envision unexpected scenarios. The broadening of thought which is then tightened in focus through discernment.

Then there’s the third mode of thinking—the creative processes that introduce new ideas and things into the world in a manner that’s original and bold. We often call this invention or innovation. The kind of “beauty” I’m interested in is the magic that arises from the interplay between these three modes of thinking.

Generally, when I make the decision to buy an artwork, I have yet to discern why the piece has its hooks in me. The work I love most often distorts or plays with my perceptions of objective reality, or perhaps enables me to explore and question my own sense perceptions and view of the world. They tend to be works that spark wonder and that instinct to discern—not to go looking for answers, but to make it clear there are ideas, endless layers of ideas, to explore.

— Dr. Jonathan Brotchie